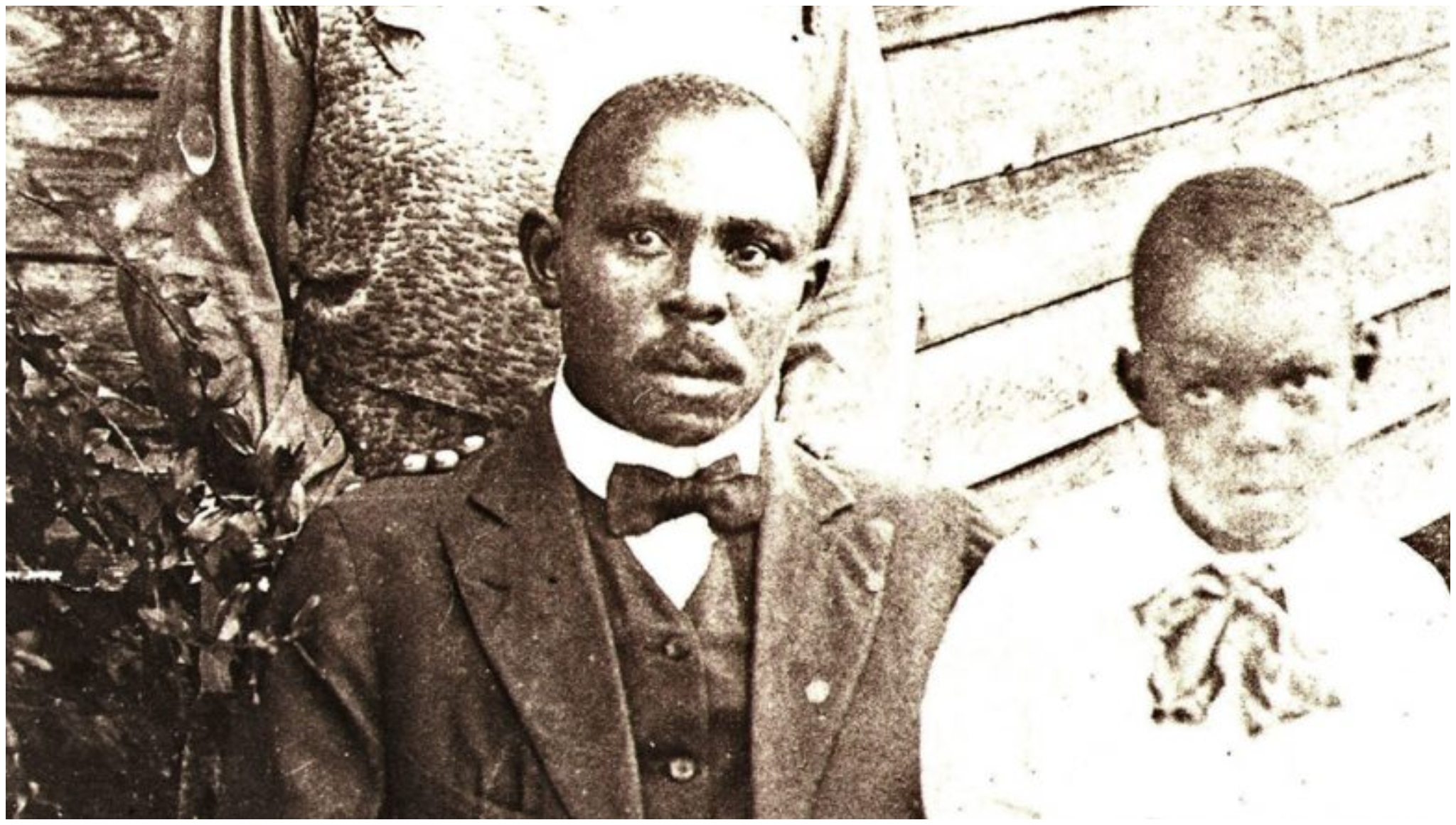

Honoring Osborne Brooks in Greenwood Cemetery

On a quiet fall afternoon, a group stood near the grave of Osborne Brooks. They listened closely as a guide shared stories of his life and legacy. Brooks, born in 1915, lived in Jonestown—Orlando’s first African American neighborhood.

His grave lies in section three of Greenwood Cemetery. Nearby rest his aunt, Isabell Demps, and his mother, Sophronia Brooks, who is buried in an unmarked grave. These resting places mark not just lives, but a community nearly erased from memory.

Greenwood Cemetery and Segregation in Death

Greenwood Cemetery was once one of the few places in Orlando where both Black and white residents were buried. But segregation still ruled. Black burials were pushed to the farthest sections.

When the city bought the cemetery in 1893, it passed laws enforcing burial segregation. As the cemetery grew, Black burial areas kept moving north, bordering Jonestown. Even in death, Orlando’s Black residents were kept out of sight.

Osborne Brooks Born in the Floodwaters of 1915

In October 1915, just a month before Brooks was born, heavy rains flooded Jonestown. Homes were nearly submerged. While newspapers covered the loss of pigs from a white landowner’s farm, they ignored the people who lost their homes.

Brooks entered the world in the middle of this disaster. A month later, thousands of frogs filled the flooded streets. His early life mirrored the hardships his community faced, even from nature.

A Childhood of Struggles and Strength

Osborne’s parents, Bert and Sophronia Brooks, both worked at the South Florida Foundry. They lived on East South Street, a key part of Jonestown. Osborne likely studied at the “Colored School” on Newman Avenue.

Tragedy struck in 1929 when Sophronia died of pneumonia. She was buried in “strangers’ row” of section K, another segregated part of Greenwood. Bert moved to Jacksonville for work, leaving Osborne with his aunts.

Life Under the Shadow of Racism

In Osborne’s youth, the Ku Klux Klan resurfaced in Orlando. In 1931, they marched near Jonestown during a public parade. Racism wasn’t hidden; it was loud and on display.

Three years after his mother’s death, Osborne became an orphan. His father died in 1932 and was buried in an unmarked grave. Osborne stayed strong. In 1933, he graduated from Jones High School, one of the first classes to finish 12th grade there.

Jonestown Faces Erasure

By the 1930s, Jonestown faced serious pressure. White homeowners wanted the area gone. The city took over Magruder’s land—30 acres of Jonestown—to expand the cemetery.

In 1939, fires, protests, and a collapsing sinkhole added fuel to the city’s push to remove Black residents. Slowly, Jonestown was emptied, home by home. Churches and houses were destroyed.

A Soldier in the Fight for Equality

Just weeks before Pearl Harbor, Osborne joined the U.S. Army Air Force. He served in the “Double Victory” campaign—fighting fascism abroad and racism at home.

As a sergeant in Squadron C of the 336th, he led teams and managed crucial military operations. Though segregation ruled the military, Osborne proved his strength through leadership and service.

Return to a Changed Orlando

When Brooks returned from World War II, Jonestown was fading fast. By 1951, only 11 families remained. Osborne and his aunt moved to the Holden neighborhood, where he worked at the Orlando Drive-In Theater.

By 1962, the last two families had left. The city bought their properties. Jonestown, once vibrant, was officially gone.

Final Days and Ongoing Legacy

Osborne Brooks passed away in 1965 at age 49. He was buried in the same segregated cemetery where his story began. A few years later, the city repealed its rule separating graves by race, after a push from the NAACP.

Today, Osborne Brooks is part of a cemetery tour. His story reminds Orlando of its past and the people who lived, struggled, and served. Jonestown may be gone, but through Brooks’ life, it is never forgotten.

Leave a Reply