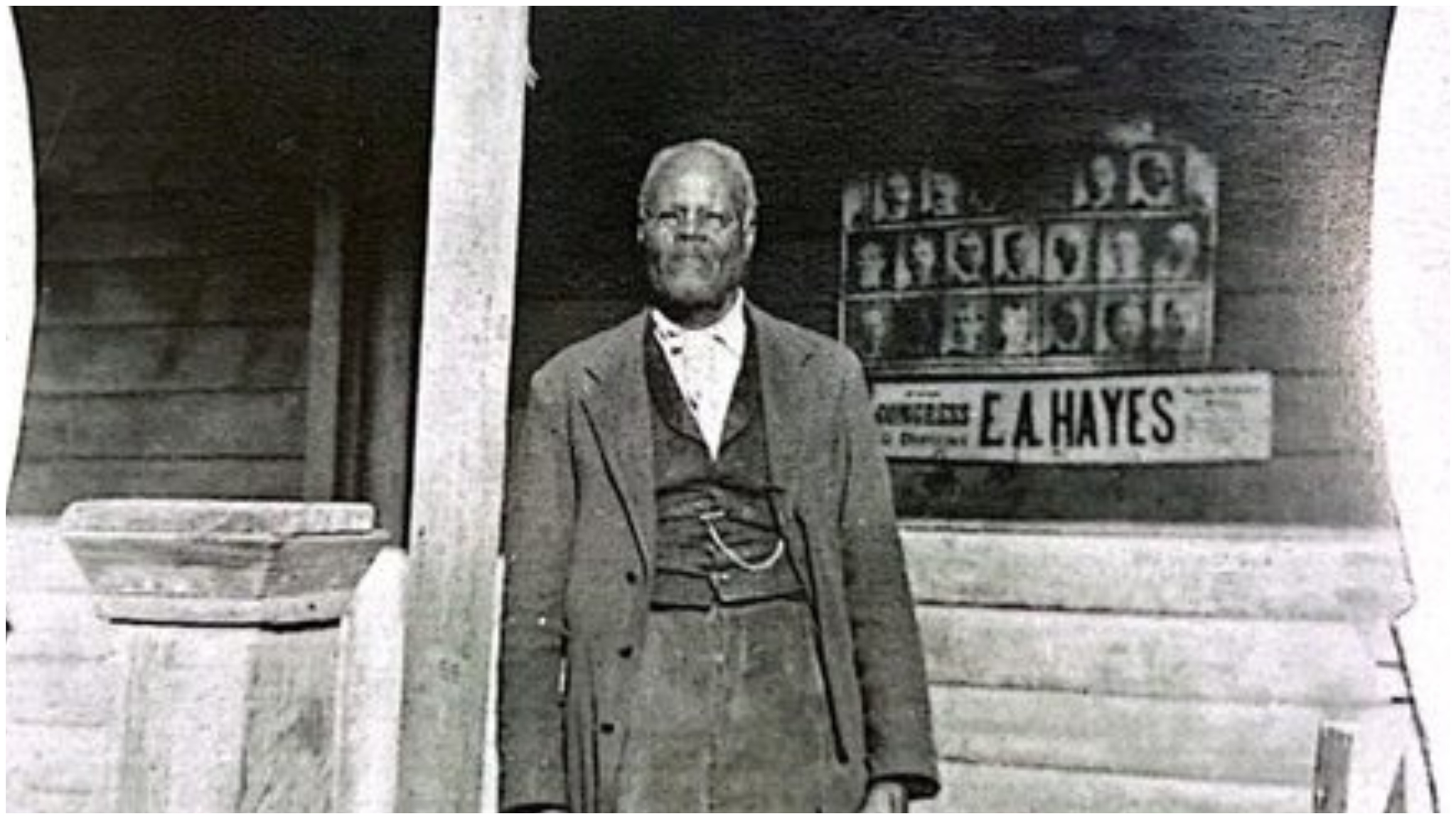

James Williams, born into slavery in Georgia in 1825, overcame extraordinary obstacles to become Santa Clara’s first African American citizen and a respected community leader. Known affectionately as “Old Jim,” Williams purchased his freedom after forced labor in California’s gold mines and went on to establish himself as a successful entrepreneur and dedicated public servant. His remarkable journey from enslaved person to honored community figure exemplifies resilience and determination during a turbulent period in California history.

Today, Williams’ legacy lives on through a memorial plaque at the Santa Clara Fire Department headquarters, recognizing his significant contributions to the volunteer fire service. Without the Garden City Women’s Club’s determination to document African American history in 1976, however, his inspiring story might have faded from public memory.

From Georgia Slavery to California Gold Fields: A Journey to Freedom

Born April 1, 1825, in Georgia, James Williams’ life changed dramatically when he was forcibly brought to California as a slave in 1851. His owner compelled him to work in the Sierra Nevada gold mines near Negro Hill, an African American mining settlement. Despite these harsh circumstances, Williams managed to earn enough money to purchase his own freedom.

Unfortunately, Williams’ path to independence wasn’t smooth. After being swindled out of $600, he realized gold mining offered few guarantees. Like many others during this period, he sought more reliable opportunities beyond the uncertain prospects of the gold fields.

This pivotal decision led Williams to Sacramento, where he began building a new life as a free man. He became a respected community member, eventually being appointed agent and trustee for the AME Church of Sacramento. His connection to this institution highlights his early leadership roles in California’s African American community.

Entrepreneurial Success and Historical Documentation Through Personal Writing

Williams proved himself a savvy businessman after settling in Northern California. By 1870, records show him living at Murphy Ranch in Milpitas. During this period, he established a successful whitewashing business and operated profitable freight teams between Hollister and San Francisco.

Beyond his business acumen, Williams demonstrated remarkable foresight by meticulously documenting his experiences. In 1874, he published an autobiography titled “Life and Adventures of James Williams.” This rare historical document, now a valuable collector’s item, originally sold for just 55 cents per copy.

Through his writings, Williams provided firsthand documentation of African American experiences during California’s formative years. His journal-keeping habits preserved crucial insights into a perspective often overlooked in mainstream historical accounts. Today, his autobiography serves as an invaluable primary source for understanding early Black California history.

Friendship and Community Bonds in Santa Clara Valley

Williams’ move to Santa Clara came through his friendship with State Senator Frederick Franck. While the exact date of his relocation remains unclear, their close relationship proved crucial to Williams’ life in the South Bay. After Williams experienced “business reverses,” Franck invited him to live in a house near what is now Santa Clara City Hall.

The depth of this friendship extended beyond Senator Franck’s lifetime. After the Senator’s death, his children Frederick Jr. and Caroline Johnson continued caring for their father’s friend. This ongoing connection speaks to Williams’ character and the genuine bonds he formed in the community.

Williams quickly became an integral part of Santa Clara society. The local Fire Department recognized his contributions in 1893 when they elected him sergeant-at-arms for the “Hope Hose Company.” This honor reflected both his commitment to public service and the respect he had earned among his fellow volunteers.

A Beloved Figure in Early Santa Clara Community Life

In his later years, Williams became a familiar and cherished presence around Santa Clara. Chronicler Stephanie Menzies captured his daily routines: “In his last years, ‘Old Jim’ puttered around a vegetable garden from which he extracted his finest products to give to friends.”

People throughout town recognized his distinctive appearance as he “hobbled around town with the aid of a cane, his spectacles reflecting the light rays, inviting conversation.” Williams was known for his memorable response when someone expressed doubt during conversations. According to Menzies, he would “square his shoulders and declare seriously: ‘Good Lord, man do you think I’d lie to you?’”

These personal details reveal Williams as more than just a historical figure. They paint the portrait of a principled man who valued honesty, generosity, and connection with his community. Despite the racial barriers of his era, Williams clearly earned widespread affection and respect among Santa Clara residents.

Preserving Black History Through Community Determination

Williams’ story might have been lost without dedicated efforts to preserve African American history in Santa Clara County. In 1976, the Garden City Women’s Club took action after noticing the exclusion of Black history from a San Jose Bicentennial publication. Their research resulted in “History of Black Americans in Santa Clara Valley,” which included Williams’ story as retold by Stephanie Menzies.

More recent works have continued to document Williams’ contributions, including Jan Batiste Adkins’ “African Americans of San Jose and Santa Clara County.” Additionally, resources like Gabriel Frank-McPheter’s story map “Silicon Valley’s Black Population: A History of Exclusion” provide important context for understanding Williams’ experiences.

These preservation efforts highlight the ongoing challenge of maintaining diverse historical narratives. Although California entered the Union as a technically non-slavery state, its 1849 constitution denied voting rights to non-white citizens. Understanding Williams’ achievements requires recognizing the significant legal and social barriers he overcame in early California.

Honored in Death as in Life: A Legacy Remembered

Williams became ill in October 1913, prompting City Marshal George P. Fallon to rush him to Santa Clara County Hospital (now Valley Medical Center). There, on October 5, he passed away. The significance of his death to the community was evident when his obituary appeared on the cover of the October 7 edition of the Santa Clara News.

The newspaper noted that the Hope Hose Company’s flag “floats at half-mast in his memory,” a tribute to his years of service with the volunteer fire department. More recently, African American members of the Santa Clara Fire Department honored Williams’ legacy by installing a memorial plaque at department headquarters.

These tributes reflect Williams’ lasting impact on Santa Clara history. From enslaved person to respected community leader, his journey embodies perseverance against tremendous odds. Today, his story serves as a powerful reminder of the often-overlooked contributions of African Americans to California’s development and the importance of preserving diverse historical narratives.