Black Bottom was once a vibrant African American neighborhood in Nashville, Tennessee. Located near what is now downtown, it stood as a testament to the resilience and success of Black Americans in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The area played a crucial role in shaping Nashville’s cultural and economic landscape before its eventual displacement due to urban renewal projects in the mid-20th century.

The Early Roots of Black Bottom

Black Bottom was founded around 1832, initially serving as a settlement for impoverished whites, many of whom were European immigrants. The neighborhood earned its name from the periodic flooding of the Cumberland River, which left behind layers of muddy residue. This made the area less desirable for settlers but eventually became home to a small number of free Black residents and enslaved individuals.

As time passed, Black residents in Black Bottom worked as artisans, laborers, cooks, and servants. However, their ability to find stable, semi-skilled work was often hindered by competition from the European immigrants who had settled in the area. Racial tensions escalated as the Black community grew, leading to Nashville’s first race riot in December 1856. This marked a troubling chapter in Black Bottom’s early history, yet the community endured and grew despite the challenges.

A Flourishing Community During the Civil War

When Union troops occupied Nashville in 1862, Black Bottom saw a dramatic increase in its population. Fugitive slaves from surrounding areas sought refuge in the neighborhood, transforming the area into a crowded and often dilapidated slum. Despite the poor conditions, this influx of African Americans played a pivotal role in shaping the future of Black Bottom.

By 1880, the Black population of Black Bottom outnumbered the white residents. This shift marked the beginning of Black Bottom’s transformation into a thriving African American enclave. Black residents started to establish institutions that would define the area. Churches, schools, and businesses sprang up, creating a strong foundation for the community to build upon.

The Cultural and Economic Hub of Nashville

By the late 19th century, Black Bottom had evolved into an important cultural and economic hub for Nashville’s African American population. One of the key institutions was the Saint Paul African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, which provided spiritual and social support for the community. Additionally, Pearl High School, one of the first public high schools for Black students in the United States, became a cornerstone of education in the area.

The neighborhood also became home to several Black-owned businesses, ranging from an ice cream factory to clothing stores and funeral homes. This entrepreneurial spirit fostered a sense of community pride and helped sustain the local economy. Black Bottom also housed Meharry Medical College, an important institution that trained Black doctors at a time when racial discrimination barred Black individuals from entering many medical schools.

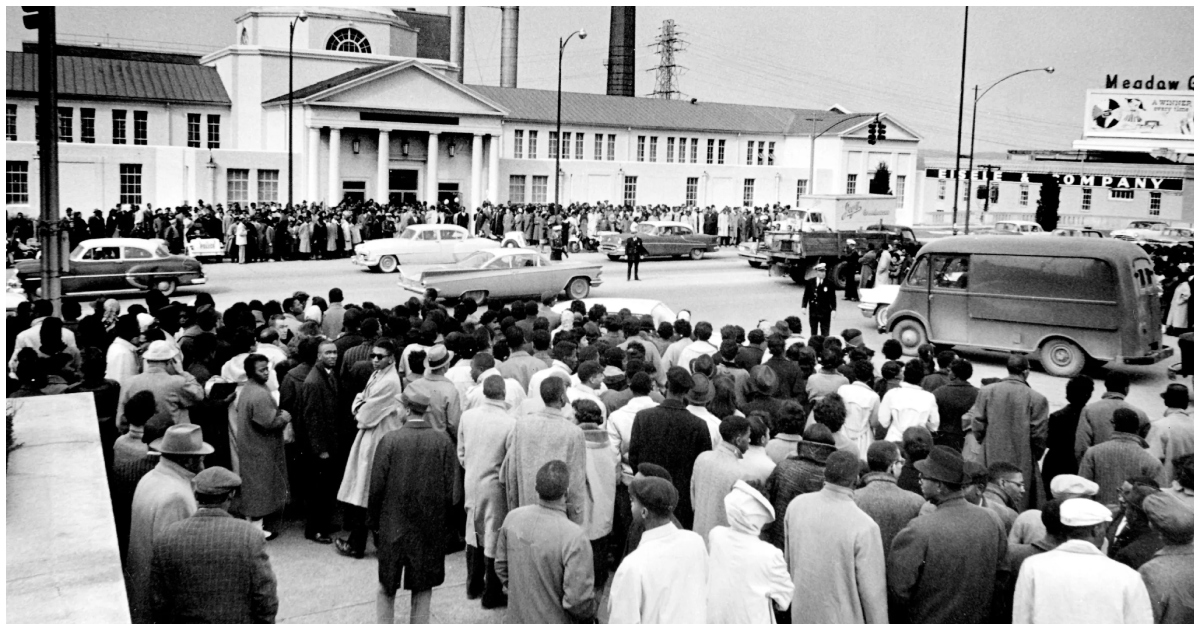

The Decline of Black Bottom in the 20th Century

Despite its cultural and economic vitality, Black Bottom faced significant challenges. Residents often complained about overcrowding, inadequate infrastructure, and the dilapidated conditions of their homes. By the 1930s, the neighborhood began to experience a period of decline. New Deal programs led to the construction of schools and recreational facilities at Tennessee A&I State University (now Tennessee State University), but they also focused on housing projects that concentrated poverty in Black Bottom.

The Andrew Jackson Housing Project, which initially seemed like a positive development, contributed to the deterioration of the area. By the time World War II ended, many African Americans had moved out of Black Bottom due to the construction of low-income housing in other parts of Nashville. The expansion of downtown Nashville and urban renewal projects displaced many Black businesses and residents, causing the once-thriving community to lose its identity. By the 1960s, Black Bottom had ceased to exist as an African American neighborhood.