Honoring a Pioneer in the Faith

The Galveston Episcopal community is set to honor a pioneering figure in the state’s religious history with the unveiling of a monument for the Rev. Thomas W. Cain. Born into slavery in 1843, Cain made history in 1888 when he became the first Black reverend in the Episcopal Diocese of Texas, leading the congregation at St. Augustine of Hippo Episcopal Church in Galveston.

“The three Episcopal churches on the island have a long history of deep partnership and connection,” said the Rev. Jimmy Abbott of Trinity Episcopal Church. “And this was one way for us to honor our shared past.”

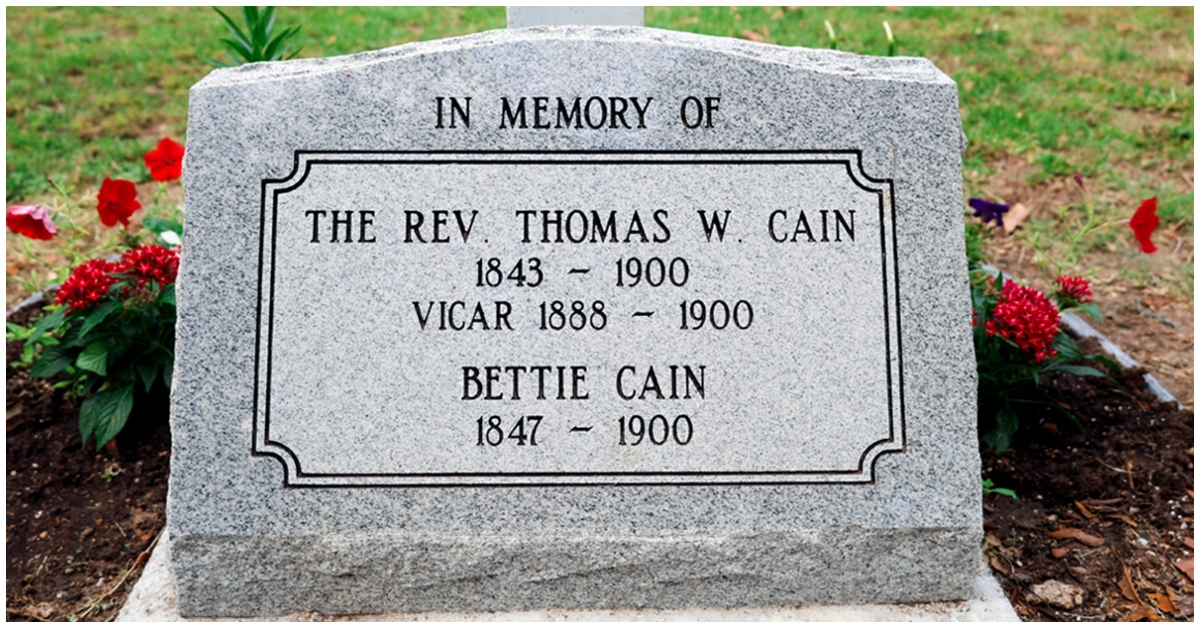

The 8-foot-tall monument, to be unveiled at Lakeview Cemetery, serves as a long-overdue recognition of Cain’s legacy, which had been reduced to an unmarked grave after the devastating 1900 Storm.

A Legacy of Progress

Under Cain’s leadership, the St. Augustine congregation flourished, raising funds for a permanent chapel and growing to over 180 active African American communicants by 1897. The church building was constructed in 1889, with the first service held on Ash Wednesday of that year.

“By 1897, there were more than 180 active African American communicants, and a church was built in 1889 in the heart of Galveston,” according to the Episcopal Diocese of Texas Racial Injustice Initiative.

Tragically, Cain and his wife, Bettie, lost their lives in the Great Galveston Storm of 1900, which also destroyed the church and rectory.

A Sign of Respect Amidst Tragedy

The fact that Cain’s body was found on the beach the day after the storm and given a proper burial, rather than being burned like thousands of other victims, speaks volumes about the respect he commanded from the Galveston community, even in those segregated times.

“That a member of the white Episcopal church found him, recognized him on the beach, and then made sure his body got reburied months later shows a great sign of respect for him,” Abbott said.

This act of reverence, before the Civil Rights Movement, offers a glimpse into the island’s relatively open nature and the Episcopal Church’s “great reverence for the past.”