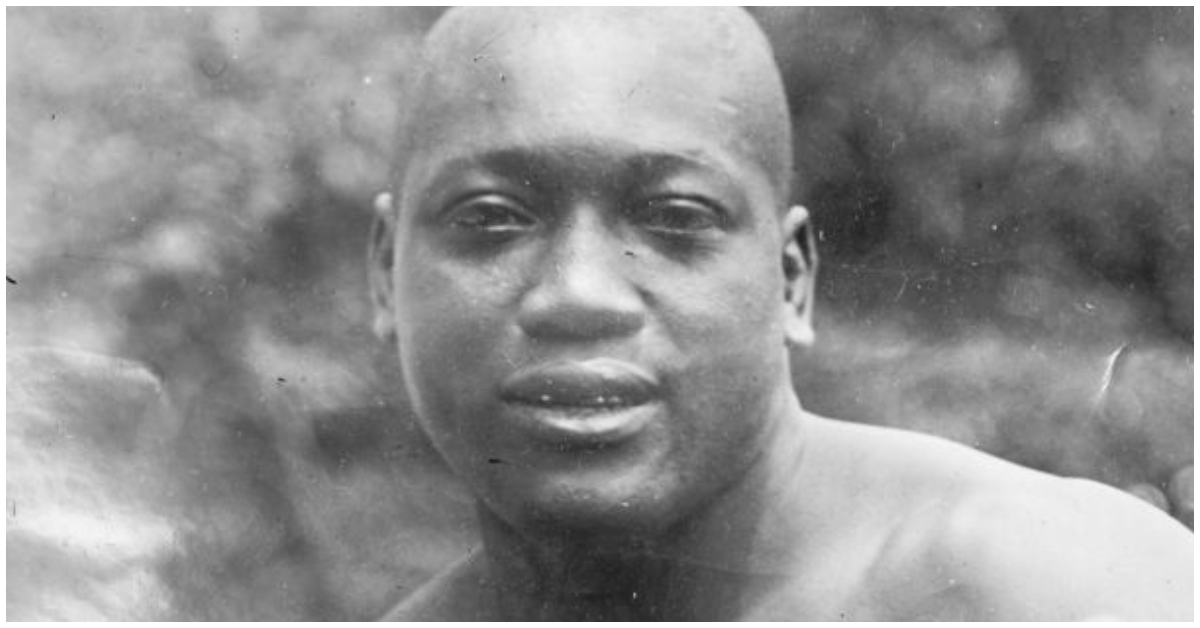

When Jack Johnson, known as “The Galveston Giant,” defeated Tommy Burns in 1908 to become the first African American heavyweight champion of the world, he transcended Jim Crow discrimination by living life on his own terms.

Growing up in segregated Texas, Johnson faced racial discrimination from an early age. However, he refused to be intimidated and pursued boxing with a determination to be the best.

After losing one of his first professional fights in 1901 to Joe Choynski, who then mentored Johnson in jail for 23 days, Johnson developed the smooth parrying and quick countering style that would become his hallmark.

He worked his way up through the ranks, eventually inducing reigning champion Tommy Burns to fight him in 1908 despite Burns wishing to avoid the matchup. In a stunning victory in Sydney, Johnson completely dominated the favored Burns and claimed the heavyweight crown after a 14th round stoppage.

Overcoming Boxing’s Color Barrier

Before Johnson’s victory, blacks and whites did not compete against each other in the heavyweight division. Johnson broke boxing’s color line and opened the door for African American fighters.

In the era of racial segregation codified by Plessy v. Ferguson, his achievement was monumental. He used his platform as champion to live life on his own terms, dating white women and driving fast cars to the consternation of many whites.

Defeating the “Great White Hope”

In 1910, former undefeated champion James Jeffries came out of retirement to challenge Johnson in “the fight of the century.” Billed as the “Great White Hope” to reclaim the title for whites, Jeffries had not fought in six years and was overmatched.

Johnson controlled the fight from the start and knocked down Jeffries for the first time in his career. After dominating for 14 rounds, Johnson forced Jeffries’ corner to throw in the towel. The victory helped solidify Johnson as an icon for African Americans.

Conviction and Late Career

Controversy continued to follow Johnson. His relationships with white women led to an unjust conviction in 1913 under the Mann Act, which banned transporting women across state lines for “immoral purposes.”

Johnson fled the country for several years before eventually returning to serve a prison sentence. After losing his title in 1915, Johnson never regained the championship belt, but he fought professionally until age 60 in 1938.

In his later years, Johnson pioneered opportunities for African American athletes and inspired icons like Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier. He proved that with determination and self-confidence, one could overcome racial barriers.

Johnson brought power and grace to the boxing ring and left a lasting legacy as a boundary-breaking champion. Though he faced considerable discrimination, he persevered to achieve greatness on his own terms.