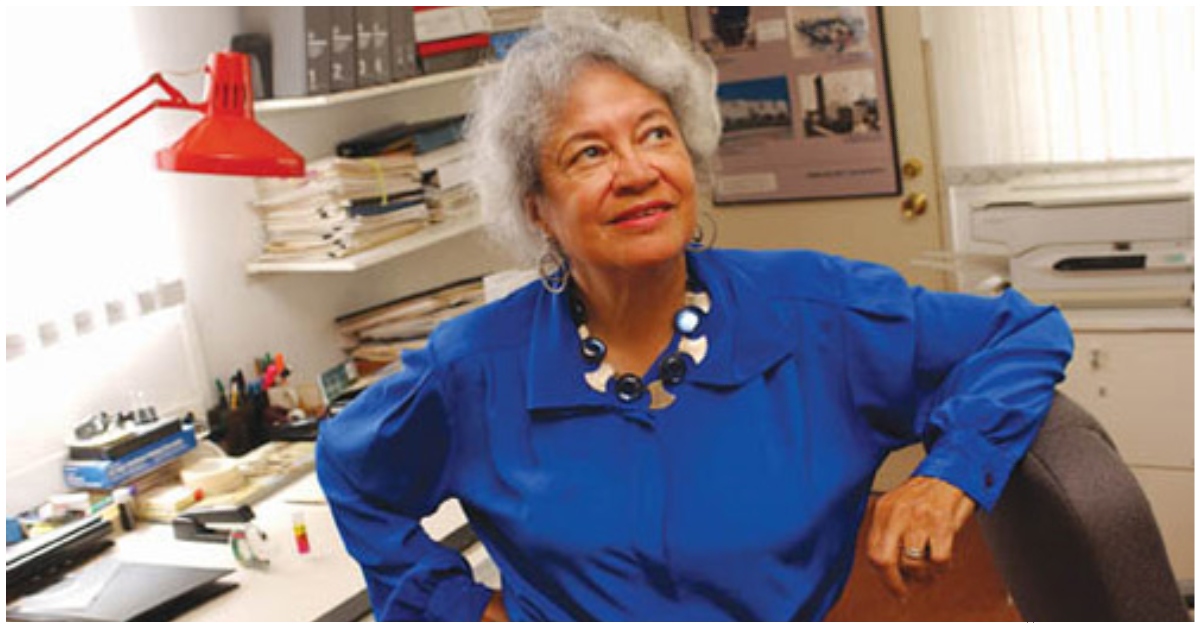

Harlem native Norma Merrick Sklarek made history several times over after earning her architecture degree from Columbia University in 1950. She smashed multiple barriers that kept Black women shut out of the profession.

In 1954, Sklarek became the first Black female architect licensed in New York state. After dealing with employment discrimination, she passed the licensing exam on her first try. Sklarek then gained experience at architectural firms in New York and Los Angeles.

By 1962, she broke another monumental color line by getting licensed as an architect in California as well. In the process, Sklarek also became the first Black female fellow of the American Institute of Architects in 1959.

Overcoming Obstacles Through Excellence

During Sklarek’s trailblazing career, the architecture field remained dominated by white men who undervalued women’s creative contributions. As a Black woman, her work frequently went uncredited despite managing notable projects like the California Mart and the US Embassy in Tokyo.

However, Sklarek persevered through prejudice and lack of acknowledgement. She leveraged her expertise to ascend to director roles that were unprecedented for an African-American woman.

Paying Knowledge Forward

A passionate advocate for diversity in architecture, Sklarek devoted time to teaching and mentoring minority students. She encouraged them to pursue licensing and helped coach them for the difficult exams she herself had passed.

In 1985, Sklarek co-founded the influential, woman-run firm Siegel Sklarek Diamond. It brought her more creative opportunities and also provided inspiration to women entering the field.

Leaving A Lasting Legacy

Even after retiring in 1992, Sklarek continued advising young architects as a lecturer and role model. With her repeated career firsts and commitment to expanding possibilities for others, she created an enduring legacy as a pioneer for women of color in architecture.

Though Sklarek was embarrassed to be singled out as the “only one” during her era, her remarkable achievements built crucial foundation for greater representation. Both her designs and mentoring efforts left blueprint for generations of Black women to find firmer footing in the profession.